By Brigitte Le Borgne

July 25th, 2019

In the course of consulting missions, we met with 2 presidents of French SMEs. The first of them, representing the second generation to rule the family company, was preparing in the medium term to transfer it to his children; the second one, who founded his company, had chosen to open the capital to an investment fund.

It was striking to discover the extent of the operational involvement of these leaders, and just how many coworkers reported directly to them.

In one case, an Executive Committee had been created very recently, in which the support functions were not represented; in the other case, there was no having any Executive Committee.

As such, it is quite paradoxical to observe that 3 French company leaders out of 4 express the need to be surrounded by either more or by better people. Moreso than sharing the capital, it turns out that sharing the management, with a real distribution of responsabilities, is indeed the best way to reduce the leader’s feeling of loneliness (1).

To understand this paradox, one must learn about the evolutions in the organisation of the company as it develops.

The impact of the steps of growth on a company’s organisation

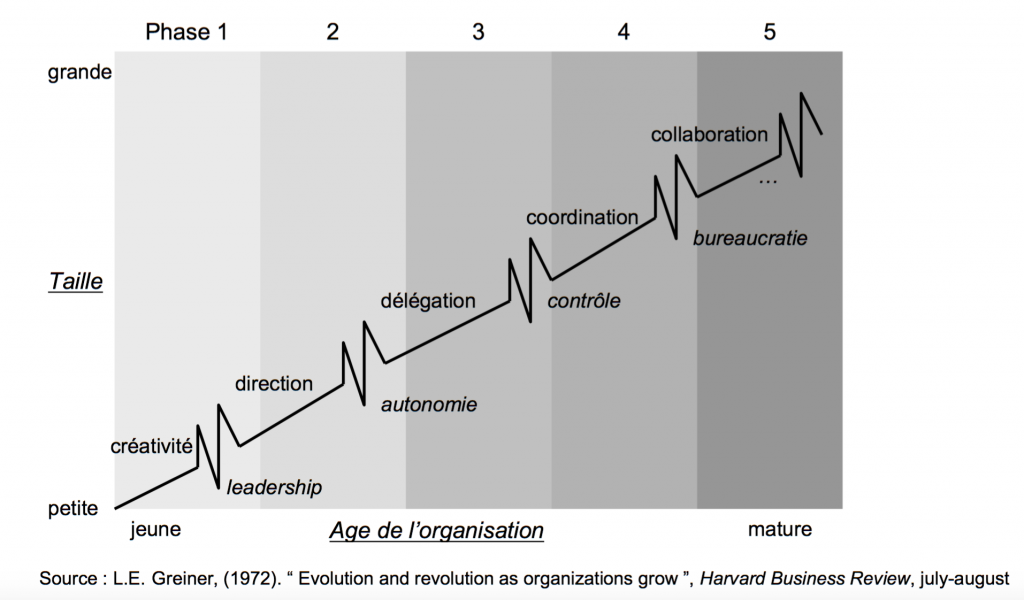

For Larry E. Greiner (2), expert in management and organisation, a company evolves through 5 stages of organization:

- In the first stage, a young company focuses its energy on launching its products or services for its target customers: this is the creativity phase. Communication between the founder and the teams is informal.

- Then, in the “scaling-up” phase, the company seeks to improve its efficiency and to secure its financial assets. Team size grows, which compels the founder to increasingly formalize internal communication.

- Progressively, the company grows in size and reaches a certain complexity, which generates a number of varied topics to deal with – especially team management – which distract him from the heart of his job and from his deep aspiration. This situation pushes the founder to set up a first role-based organisation, perhaps to recruit a chief executive: it is the management phase.

- However, the new recruits need some autonomy to drive their engagement in the company’s project. Simultaneously, the company’s growth progressiely forces the founder to manage by exception and to delegate to his managers: it is the delegation phase.

- This phase is followed by a structuring phase for the company’s governance, where an Executive Committee is set up.

The aforementioned examples prove how much passing from stage 3 to stages 4 and 5 is difficult for the President, torn between the – emotional – need to retain control and to stay the course of past successes, and the – rational – will to prepare for the future.

Especially since the leader-founder, for that purpose, surrounded himself with quality managers that wish to play a more important role in the company’s future, and may need to question his way of leadership.

The advantages of an Executive Committee

The Executive Committee enables the leader, over-solicited by topics of varying importance, to focus on those that truly create value for the company: for example, setting up the strategic roadmap for the company, also called “business plan”.

It is important that the leader has formalized his vision and has taken his team on board with him on the company’s project.

Also, the company’s project always requires change, whether industrial, organisational, or cultural (for example, any form of international development).

According to John Kotter (3), for a change to be a success, almost every director, and over 75% of executives, must believe it is absolutely necessary.

That way, the Executive Committee can enable the President to create the coalition in charge of the changes he pushes for.

Furthermore, setting up an Executive Committee, where data, analyses and decision-making processes are shared, develop the company’s flexibility and ability to anticipate, by fighting against some bias:

- As long as his ideas are challenged, the leader is better armed against the confirmation bias (the act where one places more trust in a proof that matches a belief, rather than one that contradicts it);

- Similarly, if he takes care of recruiting diversified profiles and strong personalities, he can fight against the bias of group thought (the absolute search of consensus, at the expense of a lucid assessment of alternative solutions).

Lastly, the Executive Committee gives its members the considerable advantage of having a global vision of the company and to enlight their contribution to the strategy execution, which is key in their personal engagement in the company’s project.

How to proceed? A few keys to success

Two researchers of Berkeley University (4) have demonstrated that leaders that work in groups work less efficiently than groups of subordinate coworkers: they are less creative, face difficulties in finding consensus during negotiations, and have a more conflictual relationship. Groups of leaders are more individualistic and have a tendency to hold back on sharing information.

However, such groups perform better if they work on topics that require little coordination: they then prove more creative and persistent in solving problems.

These experts recommend the leader structures the schedule and the decision processes of the Executive Committee:

- Predefined schedule

- Before making any decision, sharing information and listen to all points of view in person

In practice, we recommend, for the Executive Committee to work optimally, to limit the number of its partakers to 7, with 10 being the acceptable limit.

For that purpose, it is important to inform the Committee members about the core objectives of the Executive Committee:

- Sharing some information – we will see which further down this page;

- Making common decisions on topics affecting the company’s development and sustainability;

- Assign responsabilities when implementing a particular project.

Only the managers with a decisive impact on reaching those objectives should be enabled to participate in the Executive Committee as permanent members.

For the Executive Committee to remain efficient, its agenda must be regularly trimmed from topics that are either obsolete or that can be treated by an individual. It is especially counter-productive to allocate time to sharing information that is already available elsewhere or that do not require any comment to be understood properly.

We reiterate on that point, for in many Executive Committees, some topics are brought up “ritually” without the Committee being able to add any value. This is all the more important as the length of the Executive Committee has a direct influence on how much attention its members pay to it. In this respect, half a day seems to be the limit for efficiency.

However, the Executive Commitee can be the place where current projects progress (launching a new product brand, an acquisition, a reorganization, redesigning the company’s information system, etc.) and to share feedback on projects that have been completed, if there is no ad hoc governance for projects.

That said, we recommend setting up specific instances for piloting any long-term project, that gathers only managers that are directly involved.

Lastly, the leader’s role of presiding over the session is key: he has to assist the group in changing the course or making decisions in the most enlightened way possible, in the most productive way possible, and to make everyone accept them, even if some members do not agree with them to begin with.

Thus, it is important that the leader is aware of the functional difficulties encountered by the groups in power, for it is his responsability to ensure that everybody contributes as they must, and to ensure mutual respect in the group.

References and definitions

***

- Vaincre les solitudes du dirigeant, BPIFrance – Le Lab

- Evolution and Revolution as Organizations Grows, Harvard Business Review, 1998, Larry E. Greiner

- Conduire le changement, feuille de route en 8 étapes, John Kotter, Pearson Editions, French version, 2015

- Failure at the top: how power undermines collaborative performance, John Angus D. Hildreth and Cameron Anderson, Institute for Research on Labor and Employment, 2016

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.